Nahovway (Margaret Sinclair)

|

Note: This photo is commonly presented as Nahovway. It was found in the Seven Oaks House Museum collection and identified based on intuition by descendant and author, Donna Sutherland.

Unfortunately a historical analysis of the photo's context indicates that it likely dates from the late 19th or early 20th century -- meaning it could not be of Nahovway. Facial recognition software suggested that this may be a photo of Marak Inkster (Nahovway's granddaughter) near the end of her life (c.1900-1912) Gail Konantz (member of a descendant family), has stated that the photo is of Jane Inkster Tait (sister to Marak). "She notes that a number of people have mistakenly assumed this was a picture of Janes’ grandmother, Margaret Nahoway Sinclair." |

Nahovway and William would have 10 children together.

Sources suggest that William was a polygamist who fathered at least three other children with different women. One source also indicates that Nahovway gave birth to at least one child with another man while William was away in Europe.

In 1824, following William's death, she moved to the Red River Settlement with her daughter Mary and son Thomas. In 1827 she was married again to an Irishman named John Forbes.

She later lived at Seven Oaks with her daughter's family. Nahovway died in 1863 at Seven Oaks and was buried at St. John's Cathedral.

Sources suggest that William was a polygamist who fathered at least three other children with different women. One source also indicates that Nahovway gave birth to at least one child with another man while William was away in Europe.

In 1824, following William's death, she moved to the Red River Settlement with her daughter Mary and son Thomas. In 1827 she was married again to an Irishman named John Forbes.

She later lived at Seven Oaks with her daughter's family. Nahovway died in 1863 at Seven Oaks and was buried at St. John's Cathedral.

Almost nothing is known about her life beyond details about her father, husband, and children. Her large family led to diverse oral traditions developing in different parts of the world. Some are more reliable than others.

Writers have offered various creative explanations for the meaning of her name. The most common is that "Na-Hov-Way" translates to "Echo" or "A Distant Voice", but to our knowledge this has not been reliably verified by a language expert.

Several of her descendants are known to have been artists, noted for their fine beadwork and embroidery. One writer also associates birch-bark baskets with her descendants. These traditional skills were passed down through the generations, and we speculate that the Sinclair family style originated with Nahovway.

Writers have offered various creative explanations for the meaning of her name. The most common is that "Na-Hov-Way" translates to "Echo" or "A Distant Voice", but to our knowledge this has not been reliably verified by a language expert.

Several of her descendants are known to have been artists, noted for their fine beadwork and embroidery. One writer also associates birch-bark baskets with her descendants. These traditional skills were passed down through the generations, and we speculate that the Sinclair family style originated with Nahovway.

Captain Colin Robertson Sinclair

|

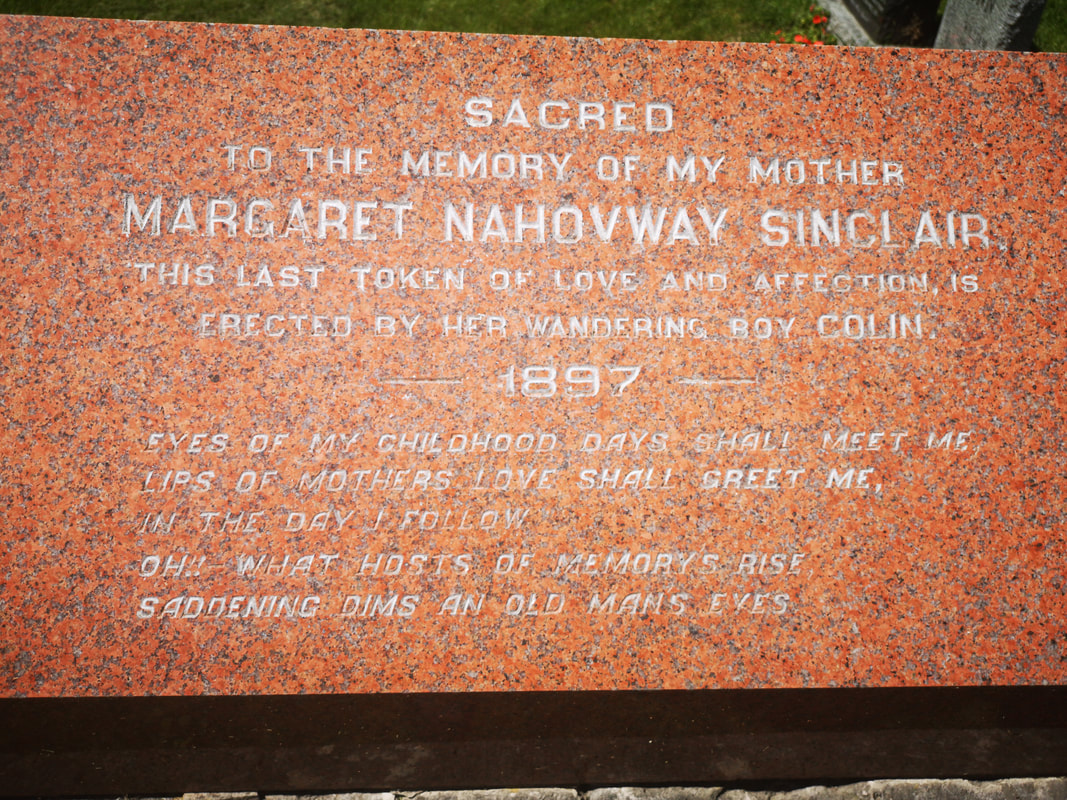

Immediately after his return, Colin erected this monument to his mother at St. John’s Cathedral. They were finally reunited when he died in 1901 and was buried next to her. His moving poem shows how deeply he regretted his choice not to return home sooner.

|

SACRED

To the memory of my mother

Margaret Nahovway Sinclair

This last token of love and affection is erected by her wandering boy Colin

-1897-

Eyes of my childhood days shall meet me,

Lips of mothers love shall greet me,

On the day I follow.

Oh!! what hosts of memorys rise,

Saddening dims an old mans eyes.

To the memory of my mother

Margaret Nahovway Sinclair

This last token of love and affection is erected by her wandering boy Colin

-1897-

Eyes of my childhood days shall meet me,

Lips of mothers love shall greet me,

On the day I follow.

Oh!! what hosts of memorys rise,

Saddening dims an old mans eyes.

|

There are conflicting interpretations of Colin's story, and we will never know the personal details of his life. Some sources who knew Colin described him as a bitter and unpleasant man, while others describe him jumping until his false teeth fell out to entertain children.

While it was common for prominent fur traders to send their Metis sons to Europe for schooling, they were typically returned in a few years with an education. Colin’s lifelong separation has led some historians to speculate that other forces could have been at work. In 'Nahoway, A Distant Voice' author and descendent Donna Sutherland indicates that Nahovway did not want her son to leave. As an Indigenous woman she would have had few legal rights, and it appears that William’s business partners were appointed as the executors of his will. There were few schools in a place like Red River, so there were practical reasons to send children away for an education. At the same time, we need to consider what this practice tells us about the way Indigenous knowledge and ancestry was viewed. The writer Alexander Ross articulated the common belief that his own Metis children needed a Christian education to separate them from their mother’s culture, so that they would develop into “respectable” men. It was considered very important that boys like Colin grow up in the image of their European fathers, and period sources make many disparaging comments about the appearance and manners of traders' Indigenous wives. These schooling practices were about both education and the suppression of Indigenous identity and culture within their children. In some respects we can see these attitudes and practices as a fore-runner to the later use of Residential Schools by the Canadian government to “kill the Indian in the child” and destroy Indigenous cultures. We will never know the specifics, but it seems clear that Colin and his mother both suffered some trauma from their separation. |

This photo was found in a family album at Seven Oaks House. It shows Jessie Sinclair Copely, Colin's niece, whose family lived in Oakland California.

|